All texts copyright Richard Shillitoe

biography

humfry payne:

“darling ithella”

In 1934 the English archaeologist Humfry

Payne was at the peak of his powers. He had

graduated from Christ Church, Oxford with

first class honours. The results of his

researches into the arts of ancient Corinth

had been published in 1931 in a thick quarto

volume, “Necrocorinthia”, illustrated with

several hundred of his own drawings, a book

that transformed scholarly understanding of the field.

Whilst this mammoth undertaking was still in progress he had, in 1929 at the age of 27, been appointed as

Director of the British School in Athens. He began to excavate at Perachora, an apparently unpromising site in

the Bay of Corinth. There, at the Temple of Hera, he had uncovered remains which came to be regarded as

among the most significant discoveries of 20th century Greek archaeology. When excavations at Perachora

concluded he began a systematic study of the ancient marbles in the museum of the Acropolis, causing a

sensation in 1934 when he demonstrated that a fragment of sculpture in the museum was an exact fit with

another fragment in Lyons museum in France, the pair forming a figure of Aphrodite. The discovery must have

been all the more sweet because, hitherto, expert opinion had been that the fragments were years apart in

date and originated in quite different parts of Greece.

In the midst of all this he found time and energy to write from Athens several times a week to a young,

unknown artist: Ithell Colquhoun. The main purpose of his letters was to entice her into his bed. The letters

are sprinkled with pet names, double entendres, and smothered in his kisses. Far from the objective, rational

scholar, he was well and truly smitten. (1)

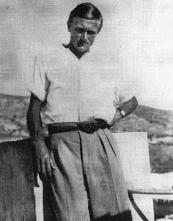

Following her graduation, Colquhoun had spent several months each year travelling through the

Mediterranean, painting and sketching the buildings and landscapes of southern France, Corsica, Tenerife and

Greece. She met Payne through Elektra Magnoletsi who had been a friend of Colquhoun’s ever since they had

studied together at the Slade. Elektra’s father lived in [or near] Athens and Elektra knew several of the

archaeologists associated with the British School. Colquhoun visited the excavations at Perachora with a

group of friends and it was there that she first attracted the notice of Payne. They met again on Payne’s trips

home to England and initially Colquhoun responded positively:

Lying in Humfry’s arms down in some country place

Called Venus’ Hill perhaps, my old green cloak under

And over us; above me his transfigured face

His neck and shoulders leaning, I look with wonder …(2)

On one of his visits home, she painted his portrait, now in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

In Payne’s letters, amongst the gossip about mutual acquaintances, accounts of his current activities and the

sharing of professional hopes and worries, he continued an extended debate with her over what each

expected (or hoped) of the other: platonic affection or physical consummation. The subject was often

approached in tortuous, earnest tones:

My Darling Ithella,

….

….I fear you think it is a poor thing to be loved with amour-goût, and rather wonder at my

having the nerve to tell you that this is what I feel. I am tempted to tell you how near I

came to the other thing just before I left England, and of the thoughts which accompanied

me on my journey here. In saying this I’m not trying to rehabilitate myself in your eyes, by

suggesting that I can do a little better than amour-goût. Because I don’t want to reach that

further stage, and I shall consider it a weakening of character on my part if I do. And I am

not in it now. But, to be quite honest with you, I don’t know how near I may come to it

again when we meet again: I hope not too near. Please tell me whether my impression that

you do rather despise this degree of affection in me is right – or if despise is too strong, and

I know it is, whether you don’t think it’s best to be liked in that way, in the circumstances –

as indeed you say that is the way that you feel towards me. I feel you may think it natural

that you should respond with amour-goût when you expect amour-passion of me.

She accuses him of inconsistency and he responds in kind:

You are equally so yourself, having twice enunciated your moral principles which prevents

you accepting me, and twice contradicted yourself afterwards.

Could the relationship with Payne have developed? It seems doubtful. Despite his reassurances that his wife

would not mind were she to find out, Colquhoun clearly felt it would be disloyal to her: after all, the women

were on friendly terms. Temperamentally, Payne and Colquhoun were poles apart. She the mystic and he the

materialist, laughing at her when she cast horoscopes or constructed talismans. The relationship degenerated

into postal bickering, until she finally broke it off, writing sternly:

It is possible that a more casual relationship would suit you better in which case you should

find someone with a temperament very different from mine. Not that I ever expected an

absolutely ‘square deal’, but I did not expect quite such an irregular polygon, and am not

prepared to put up with it.

Later, she expressed it more poetically, but with greater bitterness:

To ease his extra marital relation

Which had become in time rather a bore

He fixed his mind’s eye on a corn-haired girl

He’d hardly spoken to; wrote to implore

Her intimate companionship on a voyage.

….

To trim this polygon irregular

Into harmonious circle or ellipse

An auburn woman with no grief to share

May, gold-presented, bring apocalypse. (3)

Within months of the relationship ending Payne was dead. A minor knee injury led to septicaemia. Antibiotics

were not available and death came swiftly. Elektra married Peter Megaw, the archaeologist who took over as

acting Director of the British School after Payne’s death. She kept in touch sporadically with Colquhoun for

the rest of her life. (4) Payne’s widow Dilys Powell remarried and achieved recognition as a film critic and

writer. She, too, kept in intermittent contact, on one occasion purchasing a sketch of her late husband. She

wrote a moving account of her time with Payne, “The Traveller’s Journey is Done” in which she refers to

herself throughout as “she”, perhaps to distance herself from the persistent grief of bereavement. (5)

notes

1. Payne’s letters are at TGA 929/1/1402-1552

2. Unpublished. TS at TGA 929/2/2/9/8.

3. London Broadsheet, 1954.

4. The Megaws owned Colquhoun’s portrait of Payne, and bequeathed it to the National Portrait Gallery. The

NPG also has a pencil sketch of Colquhoun, drawn by Elektra in 1933-4. A photograph of Colquhoun and

Elektra together, in which Colquhoun wears the dress that appears in the sketch, is in the Tate archive. By

modern standards, when mild obesity has become the norm, the pair look positively skeletal.

5. Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1943.