All texts copyright Richard Shillitoe

the occultist:

the golden section

The golden section is present throughout Western culture. Mathematically,

the golden section is that point on a line which divides it into two parts,

such that the proportion of the smaller part to the larger is the same as the

proportion of the larger part to the whole line. This requires that the line

be divided at approximately 0.618 of its length.

Perceptually, the section occurs at the point where the length of the

smaller component is maximally striking without challenging or

overwhelming the larger component. Aesthetic experiments have shown

that people find the golden section proportion more pleasing than any

other. From the Great Pyramid of Gizah to the buildings of Le Corbusier,

architects have incorporated the proportion into their designs. Musicians

have incorporated it into their compositions. In ancient Greece, the

Pythagoreans took a mystical attitude towards it, possibly because, like pi,

it cannot be calculated: it extends to an infinite number of decimal places

without recurring. Plato, in the “Phaedo”, described the Pythagorean belief

that the body is maintained by a ‘tensive relation that exists between pairs

of opposites’, and that the ‘soul is a harmony’ resulting from the proper balance between opposites. A line

that is divided at the point that forms the golden section may be thought of as the unity divided into its

component parts, or opposites, to provide the greatest harmony.

Perhaps surprisingly, Colquhoun made very little use of the golden section. It can be found in only eight works,

all dating to 1939 or earlier. One would not expect to find significant dimensions such as the golden section

incorporated into automatic works, save, perhaps, in the dimensions of the paper or canvas support. And,

indeed, they are entirely absent. The conclusion must be that for a limited period only, the golden section

was designed into Colquhoun’s compositions. It has the appearance of being a stylistic experiment rather than

a method of introducing hermetic significance.

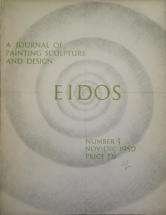

A partial exception to this conclusion is that in 1950 Colquhoun designed the cover

for “Eidos”, a short-lived journal of painting, sculpture and design that ran for only

three issues. Colquhoun’s design was based on the φ spiral. According to the

editorial in the first issue, the φ symbol was chosen to represent the eternally

recurrent rhythm of life itself: ‘being numerically related to the Fibonacci series

which is fundamental in nature and unwinding in the proportions of the Golden

Section which is fundamental in art, it has a creative as well as an historical

application.’